What Are the Essential Solo Jazz Steps (and Where Do They Come From)?

If you’ve just started learning solo jazz, you might be wondering: What are the essential solo jazz steps I should learn first? Which moves form the foundation of this vibrant dance? And where did they come from?

In this guide, we’ll explore the most important solo jazz steps every dancer should know—from their origins in African-American social dances to their place in today’s jazz scene. You’ll learn not only the what and the how, but also the why behind each movement.

Whether you’re brand new or looking to refine your basics, understanding these steps (and their history) will give you a richer connection to the music, culture, and artistry of solo jazz dance.

What Are Solo Jazz Steps?

Solo jazz steps are the foundational movements of authentic solo jazz dance—a form that developed alongside swing music in the early 20th century. They combine rhythm, style, and personal expression, often blending African-American vernacular movement with theatrical and social influences.

These steps are more than just technique. They’re a physical language passed down through generations—each one carrying a story, an energy, and a connection to the dancers who came before us.

Why Learn the Classic Steps First?

Learning the essential solo jazz steps does more than give you moves to perform—it helps you:

- Understand the dance’s musical and cultural roots

- Build strong rhythm and coordination

- Develop your own improvisational voice within a shared tradition

These solo jazz steps have traveled through time—from the streets, ballrooms, and stages of the 1920s–40s to dance floors today. By learning them, you become part of a living tradition.

And here’s the beauty: once you know the basics, you can combine, remix, and stylize them in your own way. That’s how jazz dance stays alive—through each dancer’s personal interpretation.

The Essential Solo Jazz Steps and Their History

Below are some of the most iconic solo jazz steps every dancer should know—each with its own history and personality. You’ll find them in countless jazz routines, jam circles, and improvisations.

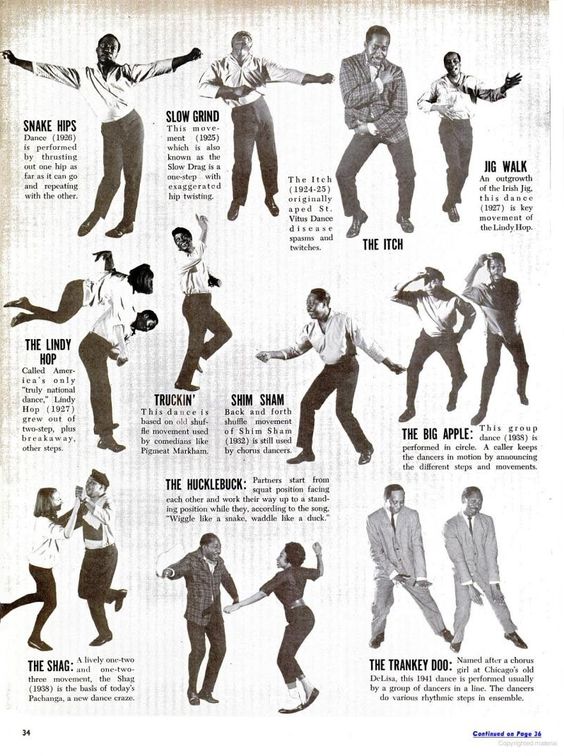

A step is already a small choreography, and its origins often reveal its flavour. Many African-derived steps have “speaking” names: some imitate animals (Camel Walk), some honour their creators (Shorty George), others simply describe the action (Shim Sham Shimmy).

Before formal dance schools, people learned on the street, at home, backstage, or in backyards—constantly searching for their own style. For Black dancers, being unique wasn’t just artistic pride, it was survival. A recognisable style could win a gig or a competition.

Signature steps were often guarded like treasures. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson famously “trademarked” his moves, shaming anyone who copied them too closely.

Sometimes dancers would teach you their step—but make sure you remembered it was their step, tied to their name. It was a way to be remembered and keep their legacy alive.

As African American tap dancer and choreographer Cholly Atkins recalls in Class Act: The Jazz Life of Choreographer Cholly Atkins:

“Years ago, you could watch the chorus lines, see all the dance steps they were doing. Eventually, somebody would lift one of those combinations and make a dance out of it—like the Suzie Q or the Boogie Woogie. I think that’s how Truckin’ came about. Maybe it started with a kid on the street, maybe a dancer in the chorus made it up. Most of the time, we couldn’t trace exactly where these authentic jazz steps came from… all we really knew was that they were here!”

Solo Jazz dance step 1 – Tackie Annie

Tackie Annie or Tack Annie is a step that was originally a tap dance step executed with brushes, shuffles and taps.

There are plenty of stories about the name origin of this typical authentic jazz move.

“Steps were normally given their names either in connection to the imitation source (animal for example) or association of the move or after the person who created them and did them better than anyone else. Shorty Snowden made up the Shorty George , and “a shuffle step known as the Tack Annie was by a pickpocket named Annie”

“Dancing, a Guide for the Dancer You Can be”

In “The World of Earl Hines”, Earl Hines, American jazz pianist, acknowledges that in Chicago during the mid – 1920s there was a woman named Tack Annie. She had a couple of girlfriends who looked after her. It appears that Tack Annie was the roughest woman he had ever seen in this life, so tough that it took several man to hold her down” (Dance, The World of Hines, p.35)

According to Harri Heinila, a Harlem jazz dance researcher, tap dancers Leonard Reed and William Bryant, who choreographed the Shim Sham, got the Tack Annie from a tap dancer called Jack Wiggins who did a thing called ‘Pull it’. He used to say to the audience: “Do you want me pull it”. The answer was usually “Yes!”.

Once he was performing to the audience, where was also his girlfriend Annie. Jack said those words again and added: “Annie next step may be tacky, but I gonna do it for you!”

Solo jazz dance step 2 – Fishtail

One of the characteristics of West – African tradition is animalistic imitations. You can definitely see it in many moves. Fishtail is one of them. The rich verbal vocabulary of vernacular black jazz dance movement as well often reflects the movement character and body usage, and in the face and hands. Look at the names of the steps such as Wing, Stomp, Fishtail, Black Bottom, Snake Hips and so on.

You can see Al Minns dancing fish tail in “The Spirit Moves” series:

Solo Jazz dance step 3 – The Charleston

Read the full article on History of the Charleston.

The Charleston dance had possibly the greatest influence on the American culture. Enslaved Africans brought it from Kongo to Charleston, South Carolina, as the Juba dance, which then slowly evolved into what is now known as Charleston. / ../ In African, however, the dance is called Juba or the Djouba. The name Charleston was given to the Juba dance by European Americans Africanisms in American Culture, p.52

The craze of the 20’s went into full swing when the choreographer Elida Webb Dawson, African- American dancer and choreographer at the Cotton Club in Harlem, introduced the Charleston in Runnin’ Wild (1923) – an American black Broadway musical comedy show. Her set of movements was accompanied by “The Charleston” tune by James P. Johnson and Cecil Mack. The characteristic Charleston beat, which James P. Johnson said he first heard from Charleston City dockworkers, incorporating the clave rhythm.

During “The Roaring Twenties”, Josephine Baker, famous black American dancer, introduced this dance to European audiences.

Charleston step has it’s eras and it changed with time and place. It started as a step with twists in a lazy sort of way , then transformed into a crazy wild kicking move.

Cholly Atkins, in Class Act: The Jazz Life of Choreographer Cholly Atkins, offers an alternative view on the Charleston’s origins:

“We think it came up from South Carolina and was introduced in the Broadway show Runnin’ Wild. But it’s more complex than that. There was constant cross-fertilisation — from street to theatre, dance hall to nightclub. All of these dances came from authentic jazz and were choreographed for the stage.”

Solo Jazz dance step 4 – Fall Off The Log

“Fall off the log (falling-off-the-log / falling off a log)- twisting movement consisting of shuffles and the alternate crossing and recrossing of one foot over the other, the body leaning sideways – “Brotherhood in Rhythm”

Falling-off-a-log is as well described as a step similar to Buffalo tap dance step but with a leaning pause added). It is a so- called travel step. The main rhythmic idea of the step is accentuating the backbeat on the kick. In that moment the whole body gravitates to the ground. The art of mimicry and imitation is strongly developed in black dances. Falling off a log imitates this actual process of the falling.

Solo Jazz dance step 5 – Suzy Q

Susie Q, Suzie Q or Suzy-Q is a vernacular dance step, with a shuffling and sliding step (as well performed in tap) that was introduced at the Cotton Club in 1936. The origin of the name “Suzie Q” is uncertain. There is a the reference to the name in the 1936 song Doin’ the Suzie-Q by Lil Hardin Armstrong

You can see Suzie Q performed by Al Minns, Pepsi Bethel, Leon James, Ester Washington, Sandra Gibson in The Spirit Moves film:

Solo Jazz dance step 6 – Camel Walk

“The dances of the enslaved population were often named and choreographed after the movements of animals”

(Ring Shout, Wheel About)

Camel walk is one of them. It is a solo jazz dance step that is closely resembling the knock – kneed gait of a camel.

Solo Jazz dance step 7 – Boogie back

Here is an amazing solo jazz dance step that has several layers to it. You can make it with loads of body movement and vibration and as well try to swing it by adding the already familiar kick ball change, swinging 8th step. The intention of the step is toward the ground, the earth or to the feet of other dancers, to support the fire and energy in the jam circle or cypher.

Solo jazz dance step 8 – Shorty George

The Shorty George, a signature step of Lindy hop and jazz, was named after an African -American jitterbug and Lindy hop dancer “Shorty” George Snowden (4 July 1904 – May 1982) in the 1930s. He could do this step underneath his partners legs.

Snowden was an acclaimed dancer at the Savoy Ballroom. The story is interesting. George Snowden was a short man, only about 5 feet tall and he had quite an impressively tall dance partner called Big Bea It was their “thing”, the feature. They really crafted their dance art around his height. George would jump in a split to have Big Bea turn under arms.

Shorty is often given credit for giving Lindy Hop its name. After Charles Lindbergh’s (known as “Lucky Lindy”) as the newspapers said “hopped” across the Atlantic, there was a charity dance-marathon in New York City in 1928. A reporter saw Snowden break away from his partner and improvise a few steps. “What was that!?” he asked. Snowden thought for a few seconds and replied, “I’m doin’ the Hop…the Lindy Hop”. And so the name stayed. (source Savoy Style)

In jazz dance only when the film production became more popular the forms and style started to be documented.

Solo Jazz dance step 9 – Applejack

Apple Jacks, Applejack (dance) is a jazz dance step developed in 1940’s

“Applejack (1930s–1950s) liquor, especially bootleg liquor, so called because apples were used as the main ingredient. Applejack n. (1950s–1960s) all-purpose tag name for dances”

(Juba to jive: the dictionary of African-American slang, p.10)

Solo Jazz dance step 10 – Half Break

Rhythm break steps are certainly a characteristic of the African dance tradition. In Tap and jazz half break is a step on 4 beats and starts on a backbeat. Break steps are the ones that are normally performed at the end of the jazz phrase or form, to seal or finalise the phrase. The success to perform this step is release. Remember, the great African American composer Duke Ellington said “In jazz we don’t push it, we let it fall”. Keep it in mind when doing ball change, which is a swinging 8th note. To syncopate it needs a drop. All the rhythm break steps want to gravitate to earth.

Solo Jazz dance step 11 – Full Break or T.O.B.A break

Another name for this step is T.O.B.A. break. T.O.B.A. break was a part of Shim Sham live choreography created by Leonard Reed and Willie Bryant around 1927. The break is an 8-count step and therefore carries a “second” name “full break”.

T.O.B.A. stands for Theatre Owners Booking Association. It was a black vaudeville circuit that developed and promoted black talent and catered to black audiences in the 1920’s. Among black dancers the acronym TOBA was read as “Tough on Black Actors”.

Here is Chester Whitmore, American dancer, musician and choreograoher, protege of Fayard Nicholas (of the Nicholas Brothers), showing and talking about versions of T.O.B.A break:

Solo Jazz Dance Steps as Improvisational “Break”

“Improvisation, for the Black idiomatic dancer… is the key element in the creation of vernacular dance. From the 19th-century cakewalk through the Charleston of the twenties and the Lindy hop of the thirties and forties, Black dancers inserted an improvisational ‘break’ that allowed couples to separate… for maximum freedom of movement.”

(The Routledge Dance Studies Reader, p.232)

Couple dances in African American traditions — like cakewalk, Charleston, Lindy hop, shag, and foxtrot — are derivatives of European forms. In West Africa, there’s no tradition of close embrace dances. Dancing apart allows for a better dialogue with the music.

Through improvisation, experimentation, and imitation, early African American Lindy hop pioneers created a style uniquely their own — a couples dance full of breakaways and solo moments for individual expression.

This emphasis on solo dancing is central to Jam Circles, where dancers step into the spotlight, often at fast tempos, to show virtuosity, style, and personality — a tradition rooted in African ring shouts and circles.

“Ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it.”

Style, musicality, and personality are the heart of jazz. Jazz is alive — it calls for innovation, freshness, and creativity. Knowing classic steps and their origins is essential for moving forward.

A good dancer “converses with music, clearly hears and feels the beat, and uses different parts of the body to visualise the rhythm.” (Steppin’ on the Blues, p.15)

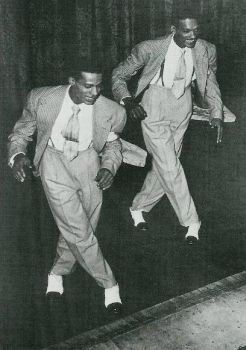

To me, this video of Albert (Al) Minns and Leon James partying says it all — who wouldn’t want to own the floor like these two?

Want to Learn These Solo Jazz Steps in Action?

If you’re ready to go beyond reading and start dancing these steps, I’ve created a complete beginner-friendly program:

In this course, you’ll:

- Learn the most important solo jazz steps from the ground up

- Understand their history and cultural context

- Practice drills and combinations to improve rhythm, musicality, and style

- Gain the confidence to use them in improvisation or performance

Whether you’re just starting or filling in the gaps in your foundation, this course is your essential roadmap to the world of solo jazz.

About Ksenia Parkhatskaya

Ksenia Parkhatskaya is an internationally renowned jazz and Charleston dancer, choreographer, and educator. Known for her viral performances and in-depth teaching, she has inspired thousands of dancers worldwide to explore the artistry and history of jazz dance. Through her online school, Secrets of Solo, she helps students not only master technique but also connect deeply to the music, culture, and self-expression at the heart of the dance.

Sources:

- Steppin’ on The Blues The Visible Rhythms of African American dance by Jacqui Malone

- Ring Shout, Wheel About: The Racial Politics of Music and Dance in North American Slavery By Katrina Dyonne Thompson

- Hot Feet and Social Change: African Dance and Diaspora Communities edited by Kariamu Welsh, Esailama Diouf, Yvonne Daniel

- Tappin’ at the Apollo: The African American Female Tap Dance Duo Salt and Pepper By Cheryl M. Willis

- Class Act: The Jazz Life of Choreographer Cholly Atkins by Cholly Atkins, Jacqui Malone

- Jazz Dance: A History of the Roots and Branches edited by Lindsay Guarino and Wendy Oliver

- Choreographing Copyright: Race, Gender, and Intellectual Property Rights in American Dance By Anthea Kraut

- African Dance: An Artistic, Historical, and Philosophical Inquiry edited by Kariamu Welsh-Asante

- The Routledge Dance Studies Reader edited by Alexandra Carter, Jens Giersdorf, Yutian Wong

- Meaning in Motion: New Cultural Studies of Dance by Jane Desmond

- Africanisms in American Culture edited by Joseph E. Holloway

- The Jazz Cadence of American Culture edited by Robert G. O’Meally

- Juba to jive: the dictionary of African-American slang by Clarence Major

- THE SPIRIT MOVES: A History of Black Social Dance on Film Screener by Mura Dehn in 3 parts:

- Part 1 Jazz dance from turn of the century ’til 1950 (44 min.)

- Part 2 Savoy Ballroom of Harlem, 1950’s (34 min.)

- Part 3 pt. 2: Postwar era, 1950-1975 (40 min.)